William Newman was on the run.

And right after his escape from the New Haven County Gaol in January 1816, bulletins went out across Connecticut, Massachusetts, and New York warning residents that a dastardly criminal was on the loose.

The Connecticut Journal was the first to break the news.

One of the most accomplished villains that disgraces our country broke from the jail in this city on Friday evening last, between the hours of five and six, and succeeded in making his escape. This fellow calls himself William Newman, and was bound over for trial at the next sitting of the Superior Court, on the charge of burglary, having robbed the house of Mr. H. Butler of plate, money, &c. He is supposed to be an Englishman, and is undoubtedly a most profound adept in the arts of knavery and deception.

William Newman was the type of criminal that was most feared at this time: the sneak thief. Sly and cunning, the sneak thief would quietly steal into homes and hotels to rob people as they slept. It was a most disquieting kind of crime that kept people on their guard, and many were alarmed by this alert.

But while William Newman was relatively new to the area, there was something in the published warning that rang strikingly familiar.

He amused himself while in prison by making and managing a poppet-show, which he performed with such scanty means as to excite the wonder of the credulous, showing the piece of an old horse shoe, whetted on the wall of his dungeon, as the only instrument of his mechanism, and complaining only of the scarcity of timber to complete the group.

It took the New York Spectator only four days to suggest a possible connection between this escaped prisoner and the sensational story of an uncommon criminal that had made the rounds just the year before.

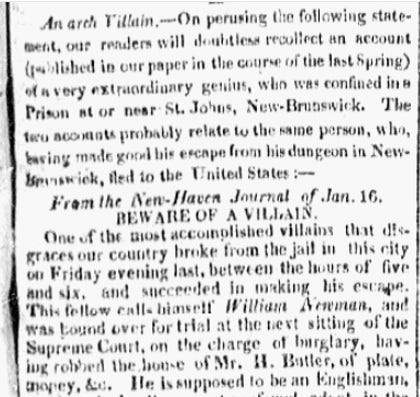

An Arch Villain — On perusing the following statement, our readers will doubtless recollect an account (published in our paper in the course of last Spring) of a very extraordinary genius, who was confined in a Prison at or near St. Johns, New-Brunswick. The two accounts probably relate to the same person, who, having made good his escape from his dungeon in New-Brunswick, fled to the United States.

Ten days later, the Connecticut Journal came to the same conclusion.

We think there is strong probability that he is the same man confined in Nova-Scotia for murder, of whom such a wonderful story was told last summer. He came to this place from Boston, and much of his plunder has been ascertained to belong to persons there.

Although the American press had misremembered a number of pertinent facts in this case – the crime was horse theft and the prisoner was confined at Kingston Gaol – they hadn’t forgotten the name of the notorious New Brunswick convict.

Henry More Smith.

Henry More Smith Goes Viral

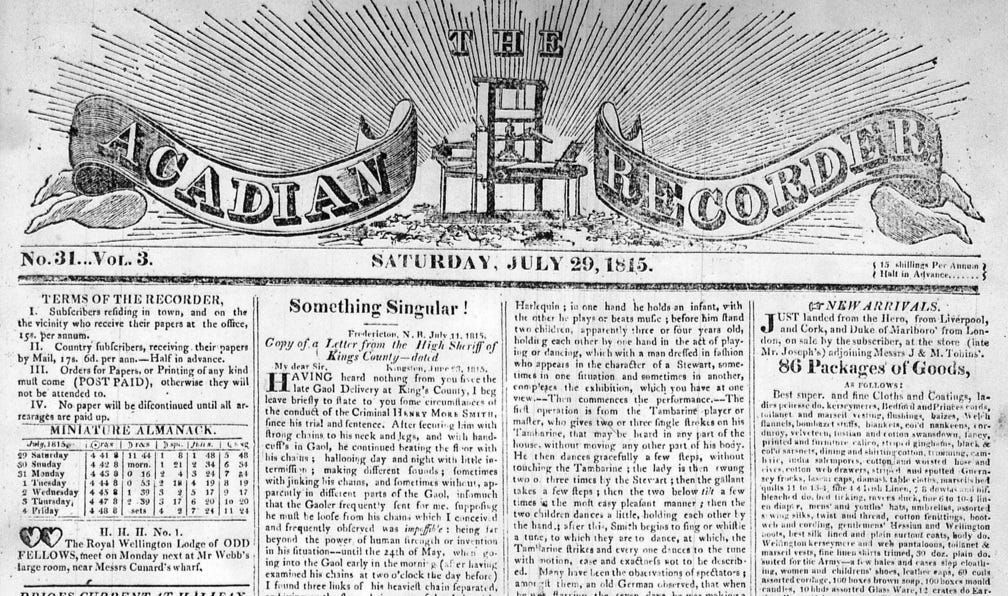

What the American press knew about Henry More Smith they learned from a letter that Sheriff Walter Bates wrote to the New Brunswick Attorney General, Thomas Wetmore, in June 1815.

Henry More Smith was convicted of horse stealing – a capital crime punishable by death – in May 1815. The Attorney General informed Sheriff Walter Bates that Henry would not be executed right away. He was concerned that the prisoner appeared unmoved by the verdict – a radical change from the displays of madness (that many thought were faked) during the trial. The Attorney General instructed the Sheriff to watch the prisoner closely and to report back about his behaviour.

As instructed, Sheriff Walter Bates paid particular attention to the prisoner who by this point had been in his custody – save for the time he escaped early in his detention – for nearly a year. The Sheriff took this opportunity to really examine this curious conman, a young man no more than 22 years old, who was by times disarmingly charming and at other times frighteningly frenetic.

Sheriff Walter Bates would describe the prisoner’s strange conduct in a lengthy letter to Thomas Wetmore – a letter that would ultimately change Henry More Smith’s fate.

Walter’s letter, dated 26 June 1815, described the impossible:

My Dear Sir –

Having heard nothing from you since the late gaol delivery at Kings County, I beg leave to state to you some circumstances of the criminal, Henry More Smith, since his trial and sentence. After securing him with strong chains to his neck and legs, and with handcuffs, he continued beating the floor, hallooing day and night with little intermission, making different sounds; sometimes with jinkling his chains, and sometimes without, apparently in different parts of the gaol, insomuch as that the gaoler frequently sent for me, supposing he must be loose from his chains, which I conceived and frequently observed was impossible, being far beyond the power of human strength or invention, in his situation; but on the 24th of May, going into the gaol early in the morning, (after examining his chains at 2 o’clock the day before,) I found three links of his heaviest chains separated, and lying on the floor, being part of the chain without the staple. He continued in the same way until the 2nd of June, when we found the largest chain parted about the middle and tied with a string, which clearly proves that irons and chains are no security for him.

This uncanny ability to break his chains had many believing that Henry More Smith was in league with the devil, for only possession by Satan himself could explain such a feat. The Sheriff then secured Henry with a chain about the neck, which he did not break. Or at least, not right away.

The balance of the letter described an astonishing creative genius, the likes of which Walter had never seen.

Walter did his best to describe what he did not understand:

But the most extraordinary, the most wonderful and mysterious of all, is that in this time he has prepared, undiscovered, and at once exhibited the most striking picture of genius, art, taste, and invention, that ever was, and I presume will ever be produced by any human being placed in his situation, in a dark room, chained and handcuffed, under sentence of death without so much as a nail of any kind to work with but his hands, and naked. The exhibition is far beyond my power to describe. To give you some faint idea, permit me to say, that it consists of ten characters – men, women and children – all made and painted in the most expressive manner, with all the limbs and joints of the human frame – each performing different parts; their features, shape and form, all express their different offices and character, their dress is of different fashions, and suitable to the situations in which they are. To view them in their stations, they appear as perfect as though alive, with all the air and gaiety of actors on the stage.

Puppets.

Henry More Smith was creating and animating – as if by magic – an elaborate troupe of puppets.

Walter would describe in great detail over many pages the electrifying performances that held audiences spellbound. The expressive faces, the articulated joints, the outfits, the dramatic storylines.

Henry More Smith would make a cast of characters – ultimately about 24 marionettes in all – from bits of bedding and his own blood. Although he called them his “family,” they did not represent his own kin. But how Henry enjoyed making his “family” dance, sing, play musical instruments, and even engage in gruesome fights (one puppet would be be-headed).

Henry performed not just for Walter and the guards, but for the curious who had heard about the shows he staged inside his cell. Small audiences paid Henry for the privilege of watching these miniature dramas unfold. Amazed audiences left convinced that Henry had been touched by Old Nick, for nothing short of the devil himself could explain such mastery.

Walter concluded his letter by insisting that Henry

has never shown any idea or knowledge of his trial or present situation; he seems happy…He, in short, is a mysterious character, possessing the art of invention beyond common capacity. I am almost ashamed to forward you so long a letter on the subject, and so unintelligible; I think if I could have done justice in describing the exhibition, it would have been worthy a place in the “Royal Gazette,” and better worth the attention of the public than all the wax-work ever exhibited in the Province.

The Royal Gazette agreed, publishing Walter’s letter in July 1815. Nova Scotia’s Acadian Recorder carried the incredible letter shortly thereafter.

And within three weeks, the American press picked it up. Walter’s letter was re-printed in at least two dozen American papers from Maine to Virginia.

Henry More Smith had gone viral.

The Predicted Pardon

What the American press did not know was that Walter’s letter to the New Brunswick Attorney General helped earn Henry clemency.

Henry’s lawyer petitioned the court asking that they take into account Henry’s youth and that this was the first instance of this type of crime in the province. But also – as Walter’s letter demonstrated – Henry possessed considerable talent and promising potential.

The arguments sufficiently persuasive, Henry would be granted a pardon once the paperwork was processed. But when Walter delivered the news to Henry, he was rather nonplussed.

He already knew, he said. A practitioner of the dark art of tea leaf reading, he could foretell the future. To prove it to Walter – a skeptic – Henry consulted a spent cup of tea on 13 August 1815. Henry said he saw three letters written about him that were soon to arrive. He predicted that shortly after their arrival he would leave the gaol, travelling by water. To prepare for his impending departure, Henry insisted he have a box to pack his “family.”

The next morning when Henry again consulted his tea leaves, he saw that the papers he spoke of would arrive that day by 4 o’clock. Walter dismissed these ramblings – Henry said so many strange things. But when the papers arrived that day as predicted – one of them containing Henry’s pardon – Walter was left startled and without an explanation.

Now spared the long walk to the gallows, Henry would appear in court one last time before his release. There Henry was quietly indifferent, paying no attention to the proceedings. But then, just before court was dismissed, Henry pulled out a puppet for one final performance.

Obviously entertained by the lively show, the judge graciously paid Henry, who pocketed the coins without comment.

A New Chapter

Two months after Sheriff Walter Bates wrote that fateful letter and two weeks after Henry’s prediction, Walter escorted Henry More Smith from Kingston to Saint John, where the former prisoner – banished from the province as a condition of his release – boarded a schooner bound for Windsor, Nova Scotia.

Walter would later learn that Henry – carrying little beyond a carefully packed box of marionettes – would blithely abandon his “family” on board without a backward glance.

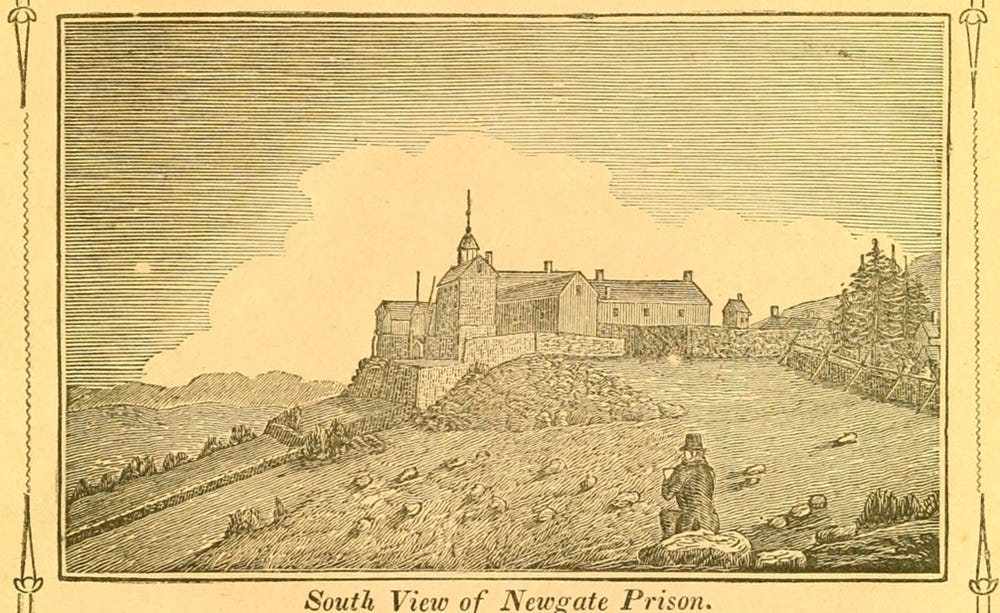

This Walter gleaned while working on his thrilling true crime book about Henry More Smith – a book that would take him to Newgate Prison in Connecticut.

To confirm whether William Newman was Henry More Smith.

Dedication

To my friends and family in Connecticut, I dedicate this cold case series.