The warden brought William Newman into the prison guard room.

And there, patiently waiting, was Walter Bates. He knew – even before entering Newgate – what he would see. And Walter prepared the warden for it, promising that though the prisoner would indeed know him, he would profess not to.

The famed prisoner now standing before him, Walter declared:

I recognized him instantly.

But just as predicted, William “maintained a perfect indifference, and took no notice” of Walter.

Until the questioning began.

Need to catch up on this case? Start here:

The Interview

Walter opened by asking the prisoner what he had done that sent him to Newgate.

Nothing,” said he, “only I had an ear-ring with me that belonged to my wife, and a young lady claimed it and swore it belonged to her, and I had no friend to speak in favour of me, and they sent me to prison.”

Next, Walter launched into a series of questions that – if answered honestly – should establish a prior connection between the two men.

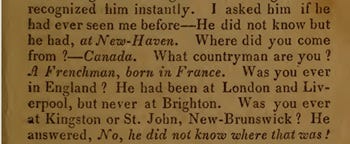

I then asked him whether he had ever seen me before.

He looked earnestly upon me and said, “I do not know but I have seen you at New Haven, there were so many men at court.”

“Where did you come from?”

His reply was, “I came from Canada.”

“What countryman are you?”

“A Frenchman, born in France.”

He had been in London and Liverpool, but never at Brighton.

“Was you ever at Kingston, New Brunswick?”

He answered, “No,” he did not know where that was.

Although the interview communicated exactly what Walter expected of his “old friend, Smith,” he was nonetheless a little impressed that the prisoner maintained a “countenance as unmoved as if he had spoken in all the confidence of truth.”

But how truthful was Walter?

Questions

The above account of Walter’s meeting with William – drawn from the third edition of Mysterious Stranger – contained curious new details.

Starting with Walter’s prediction.

Had Walter and the warden ever spoken about William Newman pretending not to know him, then why wait until 1837 to reveal that detail? Why not include it in the 1817 editions of Mysterious Stranger?

Because it did not happen.

But with this new edition, Walter clearly saw an opportunity to draw a connection between his 1816 visit to Newgate and his 1836 correspondence with William Botsford Jarvis, High Sheriff of Toronto. And the chance to establish a pattern of behaviour that – to Walter – was classic Henry More Smith.

Denial.

In Part 4, Walter was not deterred when Sheriff Jarvis declared that the prisoner then confined in the Toronto Gaol could not be Henry More Smith. If anything, the prisoner’s denials proved to Walter that he was right and that the Sheriff was wrong. And in a letter to his brother, Augustus, from March 1836, Walter insisted that the prisoner’s response to the questioning was “no more and no less, than just what, I should Expect from Henry More Smith.”

But Walter took his own expectations a step too far when he inserted a highly suspect interrogation response to the question about the crime. Especially a question that Walter did not even ask in the original interview.

Williams’s crime and capture was covered in Part 2, and an earring was never part of the list of goods William was alleged to have stolen from Butler’s Hotel. When William was searched aboard the Fulton, none of those missing items were found on his person or in his possession. And although one of the stolen items – a plate – was later found hidden below deck amongst the ship’s machinery (likely the source location of the notorious “little saw.”), William was not charged with that theft. Instead, he stood trial for stealing an earring – to which he pled “not guilty.”

Walter supplied an answer – to this previously unasked question – in the manner of Henry More Smith. Perhaps a harmless fiction, but this was not the only creative liberty Walter took in the third edition of Mysterious Stranger.

Edition Additions

When William Newman was searched while onboard the Fulton, he originally offered no resistance. But in the updated version 20 years later, William refused to open the portable writing desk that was inside his trunk. When Henry Butler could not figure out how to open the latch on the desk, he called for an axe. Rather than have his desk destroyed, William obligingly popped the tricky mechanism.

And where once Walter had lamented knowing nothing of William Newman’s trial, somehow by the third edition, he managed to paint a picture of an irate defendant who fired his legal counsel to act as his own lawyer. Though there is no evidence to support such a claim, it certainly does sound like something that Henry More Smith might do.

These and other new details spiced up the narrative with added dramatic flair.

But the inclusion of other details – intended to remove all doubt about William Newman’s true identity – are problematic.

Because they raise the red flag of reasonable doubt.

Reasonable Doubt

Alias(es)

While still in custody at the Kings County Gaol, Henry More Smith would reveal to Walter that his real name was Henry Moon, son of Edward Moon.

Walter made curious choices regarding this admission in the third edition. He decided to remove the reference to Edward Moon, but then added a fictional reflection as Henry gazed at the night sky:

On his perceiving the moon as she made her appearance between two clouds, he observed that there was a relation of his he was glad to see; that he had not seen one of his name for a long time.

Walter knew of other aliases – from a letter written by Wills Frederick Knox in October 1816 – but he only ever reproduced that letter in the second edition of Mysterious Stranger. Wills Knox, whose horse Henry More Smith stole in July 1814, pursued the young criminal from New Brunswick into Nova Scotia. Along the way, Wills noted that Henry assumed different names: “Mead, Coppigate, McDonald, and Henry Moon.” Rather than include this letter in the third edition, Walter simply summarized the account without mentioning any of Henry’s aliases.

In the third and fourth editions, Walter seemed to prefer only those aliases he had discovered through the “narrative of facts” – namely, his behavioural analysis sleuthing.

Applying this methodology – flawed as it was – Walter uncovered three potential aliases:

Henry Bond

Henry Preston

Henry Hopkins

See a pattern?

Apparently, so did Walter.

And perhaps that explains why in the third edition of Mysterious Stranger, Walter suddenly provided William Newman’s never before disclosed middle initial.

H.

Walter slipped the initial into the account of his stop at New York’s Bridewell Prison while en route to Connecticut in the fall of 1816.

On my visit to New York afterwards, I called on Mr. Allen, and enquired the particulars concerning W. H. Newman, (for this was the name he had assumed then) while in his custody.

And just like that, William H. Newman fit the Henry More Smith alias pattern.

Description(s)

When William Newman walked into the guard room, Walter declared: “I recognized him instantly.”

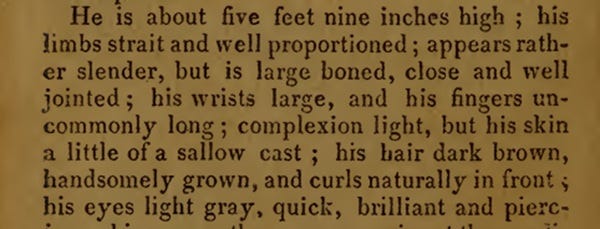

Although Walter provided an immediate and positive identification, he did admit that the prisoner had changed since he last saw him, commenting that:

He appeared rather more fleshy than when at Kingston, but still the same subtle and mysterious being.

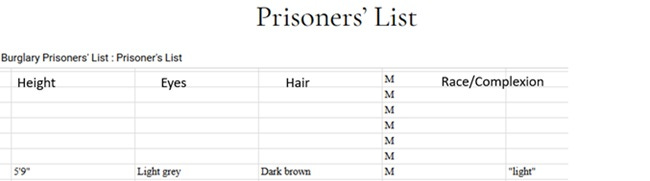

Comparing Walter’s description of Henry More Smith to Newgate’s description of William Newman, they are a perfect match.

Perhaps too perfect.

From Walter’s own narrative of facts, it is clear he did not see Henry exactly this way. He actually thought of Henry as taller than William.

The Connecticut press described William’s 5’ 9” frame as “middling stature.”

Yet, beginning with the third edition, Walter would include the vignette of a “tall stranger” who appeared in Portland on a cold and stormy night – because he believed that tall man to be Henry More Smith. And stacking up the tall evidence, Walter would increase Henry’s height in the fourth edition of Mysterious Stranger, describing him as “five feet, nine or ten inches high.”

This altered description would survive for the next two printings of the book (published after Walter’s death in 1842), before the physical description was dropped from the narrative.

However, readers of this series might have questions about the perfectly matched descriptions – because of a crucial clew presented in this series that was never printed in the book.

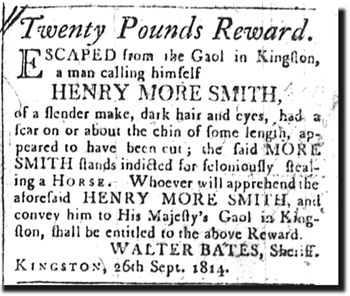

The reward notice.

The ad described Henry More Smith’s most distinctive feature.

A scar.

A scar that Walter would subtly minimize over time. From a scar of “some length,” it would eventually become a “small scar.” Reducing the significance of a distinguishing mark – once considered key to recognizing this criminal on the run – certainly raises questions.

But more troubling than the shrinking scar is the change in eye colour.

How did Henry’s dark eyes from the reward ad became the grey eyes of the prison record?

Wife and Child(ren)

Returning to Walter’s interrogation and the question about the crime brings us to the final source of doubt.

The fictional response to that question exposes gaps in Walter’s “narrative of facts.” It makes no sense for William to discuss the stolen earring. But to have him casually toss it off as his wife’s earring serves as a strange self-incrimination – admitting to having the stolen item in his possession even though it never was.

Furthermore, the fictional response demonstrates not only Walter’s familiarity with Henry but his ignorance about William. Walter knew that Henry was married – and so the wife’s earring answer made sense – but nothing was known about William Newman’s marital status at that time.

Such fictionalized additions – intended to be convincing – are rather disappointing, because they violate Walter’s “narrative of facts” methodology. A shame, because Walter had great investigative research instincts, collecting newspaper articles (all without the benefit of search engines and optical character recognition), corresponding with key figures, and conducting interviews. But preconceived notions and assumptions prevented him from digging more deeply into Henry’s return to Nova Scotia and his family.

Walter would learn – from a reportedly reliable source – that after Henry grabbed a hidden stash of goods, he left Nova Scotia. Henry apparently next turned up in Eastport, followed by Portland (the tall stranger story), before making his way to Boston. Finally, he ended up in Connecticut as William Newman – where he would be incarcerated in Newgate Prison from February 1816 until 1819.

Never once did it occur to Walter that Henry might have gone home to Rawdon to see his wife – the woman who passionately signed off her one letter to Henry with:

I remain your loving and affectionate wife until death.

Yet, Walter remained convinced that Henry never again saw his wife and daughter.

However, genealogical evidence suggests otherwise.

The Bond, Smith, and Custance family genealogies all indicate that Henry and Elizabeth had more than one child together.

Eleanor, born 1814

Winkworth/Wentworth, born 16 April 1817

Josiah, born 2 January 1820

According to the very brief Henry More Smith genealogy, found on the Family Search website, Henry died in 1821 – the only known (and as yet unverified) account of his death.

The Bond and Custance genealogies show that Elizabeth married William Custance on 20 December 1821. And upon her re-marriage, Elizabeth’s three children with Henry took the Custance name.

But the Smith name was not forgotten. When Henry and Elizabeth’s first child, Eleanor, died in 1884, the obituary remembered her as the “only daughter of the celebrated Henry Moore Smith.”

Only daughter. Not only child.

Verdict

Questions surrounding Henry More Smith’s aliases, his physical description, and his family not only provide grounds for reasonable doubt but for reasonable denial.

William Newman was not Henry More Smith.

Final Question

The how did Walter “instantly recognize” Henry More Smith at Newgate Prison in November 1816?

Find out my take on the case in The Epilogue.

Credits

I am indebted to the work of genealogists. Henry More Smith was and remains an enigmatic figure, and his research threads quickly fray. I was fortunate to locate not just one but three genealogies that reference Henry More Smith. In Rawdon and Douglas: Two Loyalist Townships, John Victor Duncanson covered both the Bond and Smith families. I was most pleased to locate online, The Custance Family of Hants, Nova Scotia, compiled by H. Douglas Goff. I searched this rich source of vital information looking for confirmation that Winkworth/Wentworth (the two names seemed interchangeable for he was listed as Winkworth in the 1871 Nova Scotia census for Hants County and Wentworth in 1881) and Josiah were Henry More Smith’s sons. I found it compelling that Josiah gave his first-born son, Joseph, the middle name “Henry.” Thrilled with this detailed genealogy, I could not resist contacting and spilling my burning research thread to Doug Goff. We had a lovely exchange and I am pleased and honoured that he is now reading this cold case true crime series. Thank you, Doug! And to the anonymous genealogist who posted the incredibly brief Henry More Smith genealogy on the Family Search website, I am grateful for the lead on Henry’s possible demise – even though I have yet to find any verification of that. Still, I will continue the search. Thank you genealogists for all you do.

Many years ago I read a book about how to create a new, false identity (this is fun reading for fiction writers or anyone who daydreams about doing this.) It was from an anarchist press that specialized in books on survivalism and extra legal activity of all kinds. One of the “tips” in the book was to take great care in choosing an alias and new persona, as almost everyone trips up in this department by leaving some vestige of a name or attribute associated with their “old” identity that would allow a clever person to connect the old identity to the new. The advice was to make sure that there was absolutely nothing - no name, backstory, taste, or habit that connected you to a former self, and that for humans this is in fact extremely hard to do.

This is a fascinating story. I greatly enjoyed reading this, and of course now has me wondering about distant ancestors who disappeared from the record and why.

Nice work! Your narrative is quite convincing.